穿孔是胆总管囊肿(choledochal cyst, CDC)的严重并发症之一,发生率为1.8% ~12%,新生儿期亦可发生[1-6]。CDC穿孔可引起重症感染、感染性休克甚至死亡,增加术中出血、副损伤的发生风险和腹腔镜手术转为开腹手术的概率[7-9]。产前诊断的CDC多无典型表现,如何预测产前诊断的CDC发生穿孔一直是临床难点。

γ-谷氨酰转肽酶(γ-glutamyl transferase, GGT)是预测CDC穿孔的重要指标,但受新生儿高胆红素血症及胆汁淤积等因素干扰,GGT单独用于预测CDC穿孔并不准确[5, 10-11]。超声是诊断CDC穿孔首选的影像学手段,但仅能对穿孔进行定性诊断,无法评估穿孔风险[12-13]。

CDC囊肿体积既往多用于鉴别胆道疾病,目前暂无CDC穿孔方面的相关应用[14]。产前诊断的CDC经历胎儿期至出生后的动态过程,需全面考虑胎儿期至生后全过程,而囊肿体积变化是能够贯穿这一动态过程的定量指标。本研究旨在初步探讨胎儿期至生后超声指标联合GGT对产前诊断胆总管囊肿穿孔的预测价值。

资料与方法 一、研究对象回顾性收集2018年1月至2023年9月就诊于首都儿科研究所教学医院普通外科,胎儿期超声提示肝门区存在与胆道相通的囊性无回声区、由术中胆道造影最终确诊为CDC的435例患儿作为研究对象。其中穿孔患儿57例,未穿孔患儿378例,手术时日龄3天至3岁18天。全部患儿自胎儿期至手术前行规律超声检查,术前未行胆道外引流手术。收集患儿产前、产后超声检查资料、术前肝功能数据和术中情况。诊断标准:CDC由术中胆道造影确诊,穿孔为术中操作者直视下确诊。

二、方法根据超声提示的CDC直径与长度计算囊肿体积,公式为:体积V(cm3)=

使用SPSS 24.0进行统计分析。对连续性变量进行正态性检验,偏态分布数据使用M(Q1,Q3)表示,组间比较选择Mann-Whitney U检验。分类变量以频数、百分数表示,组间比较采用χ2检验或Fisher精确概率法。

将患儿按3 ∶ 1的比例随机分为建模集和验证集。对建模集中P < 0.05的变量采用单因素Logistic回归分析,筛选与CDC穿孔存在关联性的变量。将筛选后变量作为自变量纳入二元Logistic回归模型进行多因素分析,构建CDC穿孔诊断模型。采用Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验及受试者操作特征(receiver operating characteristic curve, ROC)曲线评估预测效能,计算灵敏度、特异度以及最佳截断值。在验证集中对模型效能进行验证。P < 0.05为具有统计学意义。

结果建模集共纳入患儿326例,其中穿孔组43例,未穿孔组283例。穿孔组手术时日龄27.5(13,69)d,低于未穿孔组的42(18,115)d,差异有统计学意义(P=0.020)。见表 1。

| 表 1 建模集产前诊断的胆总管囊肿穿孔影响因素的单因素分析 Table 1 Comparison of various indicators between perforation and non-perforation groups in the modeling set of children prenatally diagnosed with CDC |

|

|

穿孔组患儿呕吐、发热、黄疸、茶色尿的发生比例,GGT、TB、DB、胎儿期囊肿体积增长速率,术前囊肿体积,生后至术前囊肿体积增长速率,胎儿期至术前囊肿体积增长总速率以及胆泥发生率,均高于未穿孔组,差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见表 1。

单因素Logistic回归分析显示,手术时日龄、GGT、总胆红素(total bilirubin, TB)、直接胆红素(direct bilirubin, DB)、胎儿至手术前囊肿体积总增长速率与CDC穿孔的发生存在关联性(P < 0.05)。多因素Logistic回归分析中,GGT和胎儿至手术前囊肿体积总增长速率是CDC穿孔的独立危险因素(P < 0.05)。基于多因素分析中P < 0.05的指标构建诊断模型,Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验P值为0.805(表 2)。

| 表 2 建模集产前诊断的胆总管囊肿穿孔影响因素的Logistic回归分析 Table 2 Univariate and multivariate Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing perforation in prenatally diagnosed CDC in modeling set |

|

|

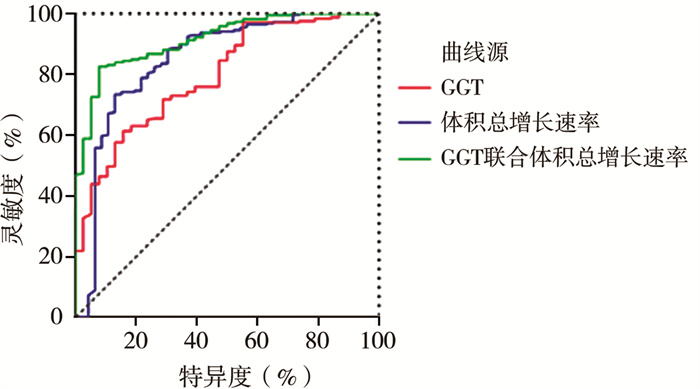

单个指标中,体积总增长率的ROC曲线下面积(area under the ROC curve,AUC)为0.849,GGT的AUC为0.796,诊断模型的AUC为0.915;诊断模型的灵敏度上升至92.1%,特异度上升至82.6%,见表 3、图 1。

| 表 3 单个指标及诊断模型对于产前诊断胆总管囊肿穿孔的诊断效能 Table 3 Diagnostic effectiveness of single indicators and diagnostic model for prenatally diagnosed CDC perforation |

|

|

|

图 1 建模集各指标诊断产前诊断的CDC穿孔的ROC曲线 Fig.1 ROC curve of various indicators for diagnosing prenatally diagnosed CDCs perforation in modeling set 注 GGT:γ-谷氨酰转肽酶; ROC: 受试者操作特征 |

验证集共纳入患儿109例,穿孔组14例,未穿孔组95例。建模集与验证集患儿基线资料对比无统计学差异(P>0.05),具有可比性。

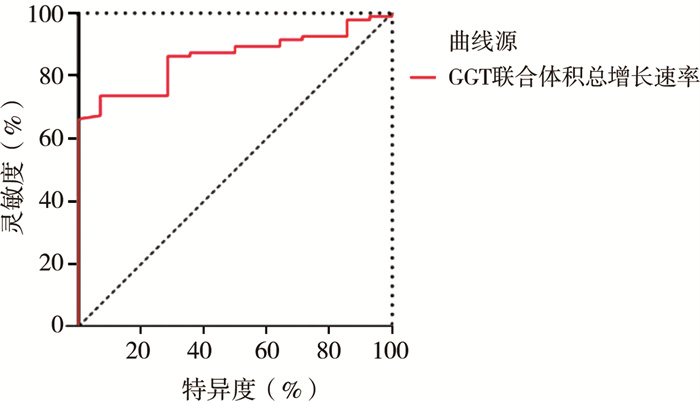

验证集患儿胎儿期至手术前囊肿体积均呈增长趋势,体积总增长速率联合GGT诊断CDC患儿发生穿孔的AUC为0.858,灵敏度和特异度分别为92.9%和73.7%,见图 2。Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验P值为0.755。

|

图 2 验证集中GGT联合体积总增长速率诊断产前诊断的CDC穿孔的ROC曲线 Fig.2 ROC curve of combined GGT and total growth rate of cyst volume for diagnosing prenatally diagnosed CDC perforation in validation set 注 GGT:γ-谷氨酰转肽酶; ROC: 受试者操作特征 |

CDC穿孔是导致术前重症感染、感染性休克甚至死亡的主要原因之一,术前穿孔会增加术中出血、副损伤的风险和腹腔镜手术转为开腹手术的发生率[7-9]。本研究中穿孔组患儿年龄显著低于未穿孔组,与既往研究提出的CDC穿孔多发生于新生儿早期,且多为产前诊断CDC观点一致[5-6]。因此,早期有效评估产前诊断CDC患儿发生穿孔的风险并及时手术治疗,对避免穿孔导致的不良后果至关重要。

产前诊断CDC穿孔患儿的症状、体征均不典型,无法准确评估穿孔风险。本研究中穿孔患儿未见典型腹膜炎征象,与胆汁性腹膜炎患者难以出现腹膜炎症状、体征的结论一致[16]。本研究还发现部分穿孔患儿出现腹部症状消失的现象,可能与穿孔导致囊肿内压力下降或新生儿难以表达腹部不适有关,与其他研究中穿孔患儿因囊肿内压力变化而存在症状波动的现象相似[8, 17-18]。目前,针对穿孔的预测指标主要集中在肝功能检查方面,但肝功能受多种因素影响,准确度依然充满挑战[11]。

超声是胎儿期筛查和出生后诊断CDC的最常用影像学手段,是生后定性诊断CDC穿孔的首选检查,但既往超声对CDC穿孔仅能诊断,且灵敏度低,不能用于评估穿孔风险[6, 12, 18-22]。既往研究发现,胎儿期和生后肝门部囊肿体积多用于鉴别CDC与囊肿型胆道闭锁(cystic biliary atresia, CBA)[14]。由于超声检查贯穿胎儿期至出生后,能够反映产前诊断CDC患儿全病程特点,为评估穿孔风险提供了可能性。本研究显示全部患儿胎儿期至手术前囊肿体积呈增长趋势,穿孔组体积增长总速率显著高于未穿孔组。CDC患儿胎儿期至手术前囊肿体积增长与胰胆管合流异常、胆总管远端蛋白栓梗阻导致的囊肿内压力增大有关[23-25]。本研究中,11.6% 穿孔组患儿和26.5%未穿孔组患儿出生后至术前囊肿体积出现下降。穿孔组患儿出生后囊肿体积下降与穿孔导致的囊肿内压力降低有关。既往研究中也提到了这一现象,并认为与穿孔组患儿症状波动存在相关性[8, 17-18]。部分患儿受到症状等因素影响而出现食欲显著下降,可能是出生后囊肿体积下降的原因之一。生后囊肿体积下降易导致误诊、漏诊。

GGT是预测CDC穿孔的肝功能指标[5, 10]。本研究中GGT是产前诊断CDC穿孔的独立影响因素,穿孔组患儿GGT显著高于未穿孔组,这与既往研究结果一致[10]。TB和DB并非CDC穿孔的独立影响因素,这与穿孔组患儿手术时日龄显著低于未穿孔组存在相关性,与Bail等[11]提出的新生儿期高胆红素血症和胆汁淤积导致肝功能异常观点一致。

本研究结果显示,胎儿期至手术前囊肿体积总增长速率是产前诊断CDC患儿穿孔的独立危险因素,AUC可达0.849,最佳截断值为每周1.00 cm3,灵敏度和特异度分别为87.0%和73.4%,说明其在评估产前诊断CDC患儿穿孔方面具有较高的效能。本研究中单独应用GGT诊断产前诊断CDC患儿穿孔发生的AUC为0.796,最佳截断值为150.85 IU/L,灵敏度、特异度分别为84.2%和61.4%。既往研究中GGT的最佳截断值为346.5~614.9 IU/L,本研究GGT的最佳截断值与之不同,可能是因为在研究时段本中心对产前诊断的CDC患儿介入较早或部分非早期介入的患儿病情较重[5, 10]。联合应用囊肿体积总增长速率和GGT作为诊断模型可将AUC值提高至0.915,灵敏度和特异度分别提高至92.1%和82.6%,HL拟合优度检验证实了联合应用两个指标区分度良好,诊断效能准确,且高于单一指标。该模型的诊断效能在验证集中得到了进一步验证。以上结果提示当体积总增长速率、GGT分别超过每周1.00 cm3、150.85 IU/L时,产前诊断CDC患儿发生穿孔的风险高,可用于预测CDC穿孔的发生。

综上所述,胎儿期至手术前囊肿体积总增长速率超过每周1.00 cm3、GGT>150.85 IU/L的产前诊断CDC患儿发生穿孔的风险高。

利益冲突 所有作者声明不存在利益冲突

作者贡献声明 论文设计为李龙、刁美;文献检索、数据收集与分析为李思源;论文撰写为李思源、刁美

| [1] |

Yamaguchi M. Congenital choledochal cyst.Analysis of 1, 433 patients in the Japanese literature[J]. Am J Surg, 1980, 140(5): 653-657. DOI:10.1016/0002-9610(80)90051-3 |

| [2] |

Ando H, Ito T, Watanabe Y, et al. Spontaneous perforation of choledochal cyst[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 1995, 181(2): 125-128. |

| [3] |

Stringer MD, Dhawan A, Davenport M, et al. Choledochal cysts: lessons from a 20 year experience[J]. Arch Dis Child, 1995, 73(6): 528-531. DOI:10.1136/adc.73.6.528 |

| [4] |

Ando K, Miyano T, Kohno S, et al. Spontaneous perforation of choledochal cyst: a study of 13 cases[J]. Eur J Pediatr Surg, 1998, 8(1): 23-25. DOI:10.1055/s-2008-1071113 |

| [5] |

Diao M, Li L, Cheng W. Timing of choledochal cyst perforation[J]. Hepatology, 2020, 71(2): 753-756. DOI:10.1002/hep.30902 |

| [6] |

Kim YJ, Kim SH, Yoo SY, et al. Comparison of clinical and radiologic findings between perforated and non-perforated choledochal cysts in children[J]. Korean J Radiol, 2022, 23(2): 271-279. DOI:10.3348/kjr.2021.0169 |

| [7] |

Lilly JR, Weintraub WH, Altman RP. Spontaneous perforation of the extrahepatic bile ducts and bile peritonitis in infancy[J]. Surgery, 1974, 75(5): 664-673. |

| [8] |

Goel P, Jain V, Manchanda V, et al. Spontaneous biliary perforations: an uncommon yet important entity in children[J]. J Clin Diagn Res, 2013, 7(6): 1201-1206. DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2013/5429.3076 |

| [9] |

Diao M, Li L, Cheng W. Single-incision laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy for children with perforated choledochal cysts[J]. Surg Endosc, 2018, 32(7): 3402-3409. DOI:10.1007/s00464-018-6047-x |

| [10] |

Zhang SH, Cai DT, Chen QJ, et al. Value of serum GGT level in the timing of diagnosis of choledochal cyst perforation[J]. Front Pediatr, 2022, 10: 921853. DOI:10.3389/fped.2022.921853 |

| [11] |

Bilal H, Irshad M, Shahzadi N, et al. Neonatal cholestasis: the changing etiological spectrum in Pakistani children[J]. Cureus, 2022, 14(6): e25882. DOI:10.7759/cureus.25882 |

| [12] |

Chen JY, Tang Y, Wang ZG, et al. Clinical value of ultrasound in diagnosing pediatric choledochal cyst perforation[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2015, 204(3): 630-635. DOI:10.2214/AJR.14.12935 |

| [13] |

Xin Y, Wang XM, Wang Y, et al. Value of ultrasound in diagnosing perforation of congenital choledochal cysts in children[J]. J Ultrasound Med, 2021, 40(10): 2157-2163. DOI:10.1002/jum.15604 |

| [14] |

Yu P, Dong N, Pan YK, et al. Ultrasonography is useful in differentiating between cystic biliary atresia and choledochal cyst[J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2021, 37(6): 731-736. DOI:10.1007/s00383-021-04886-2 |

| [15] |

张雪华, 陈文娟, 杨芳, 等. 超声在先天性囊肿型胆道闭锁及胆总管囊肿的鉴别诊断探讨[J]. 中国超声医学杂志, 2016, 32(7): 619-621. Zhang XH, Chen WJ, Yang F, et al. The value of differential diagnosis of congenital cystic biliary atresia and choledochal cyst by ultrasound[J]. Chin J Ultrasound Med, 2016, 32(7): 619-621. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-0101.2016.07.013 |

| [16] |

Chiang L, Chui CH, Low Y, et al. Perforation: a rare complication of choledochal cysts in children[J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2011, 27(8): 823-827. DOI:10.1007/s00383-011-2882-8 |

| [17] |

Evans K, Marsden N, Desai A. Spontaneous perforation of the bile duct in infancy and childhood: a systematic review[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2010, 50(6): 677-681. DOI:10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d5eed3 |

| [18] |

Chang MY, Kim MJ, Han SJ, et al. Choledochal cyst rupture with an intrahepatic pseudocyst mimicking hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma in an infant[J]. Clin Imaging, 2015, 39(5): 914-916. DOI:10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.04.016 |

| [19] |

Sherwood W, Boyd P, Lakhoo K. Postnatal outcome of antenatally diagnosed intra-abdominal cysts[J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2008, 24(7): 763-765. DOI:10.1007/s00383-008-2148-2 |

| [20] |

Thakkar HS, Bradshaw C, Impey L, et al. Post-natal outcomes of antenatally diagnosed intra-abdominal cysts: a 22-year single-institution series[J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2015, 31(2): 187-190. DOI:10.1007/s00383-014-3635-2 |

| [21] |

Lee MJ, Kim MJ, Yoon CS. MR cholangiopancreatography findings in children with spontaneous bile duct perforation[J]. Pediatr Radiol, 2010, 40(5): 687-692. DOI:10.1007/s00247-009-1447-7 |

| [22] |

Yasufuku M, Hisamatsu C, Nozaki N, et al. A very low-birth-weight infant with spontaneous perforation of a choledochal cyst and adjacent pseudocyst formation[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2012, 47(7): E17-E19. DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.03.055 |

| [23] |

Davenport M, Basu R. Under pressure: choledochal malformation manometry[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2005, 40(2): 331-335. DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.10.015 |

| [24] |

Kaneko K, Ando H, Seo T, et al. Proteomic analysis of protein plugs: causative agent of symptoms in patients with choledochal cyst[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2007, 52(8): 1979-1986. DOI:10.1007/s10620-006-9398-4 |

| [25] |

Fukuzawa H, Urushihara N, Miyakoshi C, et al. Clinical features and risk factors of bile duct perforation associated with pediatric congenital biliary dilatation[J]. Pediatr Surg Int, 2018, 34(10): 1079-1086. DOI:10.1007/s00383-018-4321-6 |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23