发育性髋关节发育不良(developmental dysplasia of the hip, DDH)是下肢常见的发育畸形之一,也是导致骨关节炎和髋关节置换术的主要原因之一,分为髋关节脱位、半脱位和髋臼发育不良,治疗的关键是早期诊断和实现稳定的同心圆复位[1-2]。虽然常用的超声髋关节筛查方法可以尽早诊断DDH,但仍有一些儿童出现延迟诊断[3-4]。对于2岁以下的患儿,闭合复位(closed reduction, CR)是DDH的主要治疗方法,而残余髋臼发育不良(residual acetabular dysplasia, RAD)是CR后主要的并发症之一,如果RAD持续存在,则需要行骨盆截骨术[5-8]。既往研究显示,髋臼指数(acetabular index, AI)、中心边缘角(center-edge angle, CEA)可以作为预测RAD是否发生的指标,但这些参数仍具有一些局限性[8-16]。MRI能够清晰显示关节软骨,并且能够进行多平面三维成像,对股骨头位置和髋臼形状的评估尤为精确。可通过观察和测量MRI上的一些参数(如头部覆盖指数、髋臼头部指数和球形度等指标)来帮助预测CR预后[13, 17-18]。本课题组前期研究发现,X线-泪滴眉弓线(teardrop and sourcil line, TSL)可以预测CR后RAD的发生,但是,X线-TSL从不连续到连续可能需要一定的时间[19]。本研究旨在初步探讨和分析DDH患儿CR术后RAD发生的影响因素,特别是探究MRI-骨性TSL在预测DDH患儿CR后RAD发生中的可行性。

资料与方法 一、研究对象本研究为回顾性研究,收集2011年10月至2019年12月于复旦大学附属儿科医院儿童骨科诊断为DDH并接受CR+石膏固定治疗的54例患儿(共68髋)作为研究对象。单侧发病40例,双侧发病14例;CR时平均年龄18个月(9~32个月),平均随访时间40.4个月(24~75个月);根据Severin分型,Ⅰ型2髋,Ⅱ型15髋,Ⅲ型46髋,Ⅳ型5髋。在40例单侧病例中,18例(26.5%)为左髋,22例(32.4%)为右髋。根据国际髋关节发育不良协会(International Hip Dysplasia Institute, IHDI)分型,Ⅲ型34髋(50.0%)、Ⅳ型34髋(50.0%)。纳入标准:①术后1周内接受MRI检查,并有连续的X线片随访;②至少随访2年。排除标准:存在神经肌肉疾病、内分泌疾病及信息不全者。本研究经复旦大学附属儿科医院伦理委员会审批通过(2019078),患儿家属均知情同意。

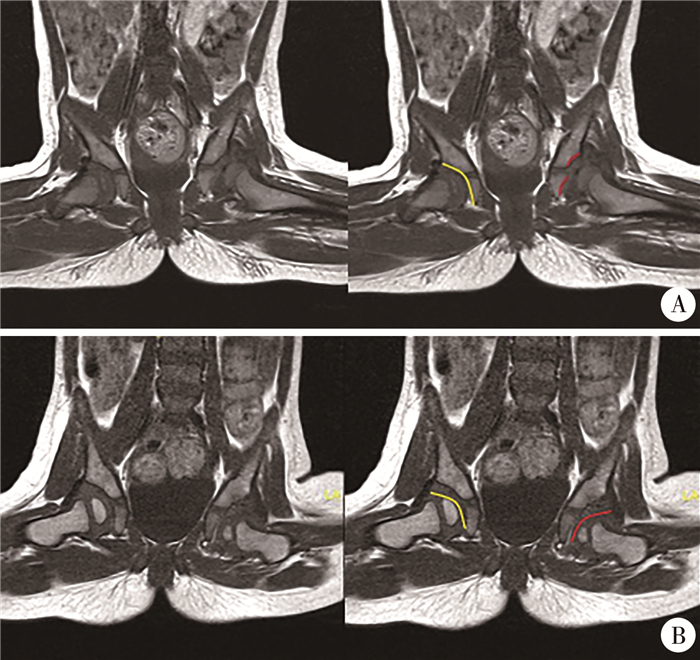

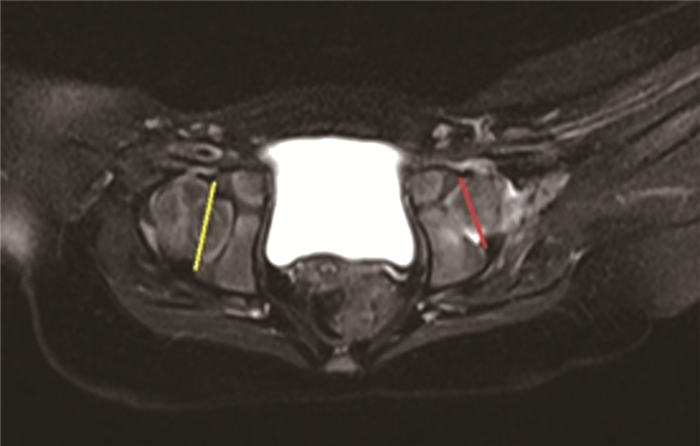

二、相关定义及分组方式泪滴线是指沿着泪滴骨(位于髋臼下方的一个小骨突)的下缘画一条线;眉弓线是指沿着髋骨的“眉弓”(即髋臼边缘的上方部分)画的一条线[19]。MRI影像上,在冠状面股骨头面积最大平面,勾勒出髋关节骨性TSL和软骨TSL(图 1A,1B);在横断面上股骨头面积最大平面,确定髋臼开口两端软骨最突出点并连线,即髋臼开口最大连线(acetabular distance, AD),见图 2。根据修改后的Severin分型[20]:Ⅰ级、Ⅱ级判定为非残余髋臼发育不良(non-residual acetabular dysplasia, non-RAD),Ⅲ~Ⅵ级判定为残余髋臼发育不良(residual acetabular dysplasia, RAD)。根据MRI-骨性TSL是否连续分为RAD组、非RAD组。

|

图 1 发育性髋关节发育不良患儿髋关节骨性泪滴眉弓线和软骨泪滴眉弓线 Fig.1 Bony and cartilaginous teardrop and sourcil lines in hip joint of DDH children 注 A:黄色曲线为正常侧髋关节骨性泪滴眉弓线, 红色曲线为患侧髋关节骨性泪滴眉弓线; B: 黄色曲线为正常侧髋关节软骨泪滴眉弓线;红色曲线为患侧髋关节软骨泪滴眉弓线 |

|

图 2 发育性髋关节发育不良患儿髋关节髋臼开口最大连线 Fig.2 Maximum acetabular distance in hip joint of DDH children |

于全身麻醉下行CR,长收肌肌腱经皮松解。随后用人位髋人字石膏固定,保持髋关节90° ~100°屈曲和40° ~50°外展。术后3天内行常规检查。3个月后,将人字石膏固定改为外展支具固定,固定时间为3~6个月。

四、资料收集及随访收集资料包括患儿CR时年龄、性别、患侧等。采用图像存档与通信系统(Picture Archiving and Communication System, PACS)成像技术测量CR时AI。通过系列骨盆正位X线片,观察TSL连续性的变化,并记录出现连续的时间。采用MRI成像技术观察和记录MRI-骨性TSL连续性;测量并记录AD长度;根据国际髋关节发育不良IHDI分型对髋关节脱位程度进行分类并记录[21]。

五、统计学处理采用SPSS 23.0进行统计学分析。服从正态分布的计量资料用x±s表示,两组间比较采用两独立样本t检验;计数资料用频数表示,两组间比较采用χ2检验。采用二元Logistic回归分析探讨DDH患儿CR后发生RAD的影响因素。将差异有统计学意义的计量指标纳入受试者操作特征(receiver operating characteristic curve, ROC)曲线运算,得到其预测RAD发生的最佳截断值、曲线下面积(area under the ROC curve, AUC)、灵敏度、特异度。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果本研究共纳入54例患儿,共68髋。其中RAD组51髋(男5髋,女46髋),CR时AI为(39.2±4.3)°,年龄为(19.0±4.6)个月,左侧27髋,右侧24髋;Ⅲ型22髋,Ⅳ型29髋;MRI-骨性TSL连续4髋,不连续47髋。非RAD组17髋(男3髋,女14髋),CR时AI为(37.6±3.7)°, 年龄(17.4±3.5)个月;左侧9髋,右侧8髋; Ⅲ型12髋,Ⅳ型5髋;MRI-骨性TSL连续12髋,不连续5髋。

MRI-骨性TSL连续组16髋(男2髋,女14髋),CR时AI为(37.5±3.2)°,年龄为(17.7±3.7)个月,左侧9髋,右侧7髋;Ⅲ型8髋,Ⅳ型8髋;4髋发生RAD, 12髋未发生RAD。MRI-骨性TSL非连续组52髋(男6髋,女46髋),CR时AI为(39.2±4.4)°,年龄(18.8±4.6)个月,左侧27髋,右侧25髋;Ⅲ型26髋,Ⅳ型26髋;47髋发生RAD, 5髋未发生RAD。

单因素分析发现,IHDI分型、MRI-骨性TSL连续性以及正常侧和患侧AD的差值是DDH患儿CR后RAD发生的影响因素(P < 0.05)。见表 1。多因素Logistic回归分析发现,IHDI分型(OR=0.090, 95%CI: 0.010~0.794)、MRI-骨性TSL连续性(OR =0.015, 95%CI: 0.002~0.128) 及正常侧与患侧AD的差值(OR=7.1×108, 95%CI: 370.6~1.4×1015)是DDH患儿CR后RAD发生的独立影响因素(P < 0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 1 影响DDH患儿CR后RAD发生的单因素分析结果 Table 1 Univariate analysis results of influencing factors for the occurrence of RAD after CR in DDH children |

|

|

| 表 2 影响DDH患儿CR后RAD发生的多因素Logistic回归分析结果 Table 2 Multivariate Logistic regression analysis results of influencing factors for the occurrence of RAD after CR in DDH children |

|

|

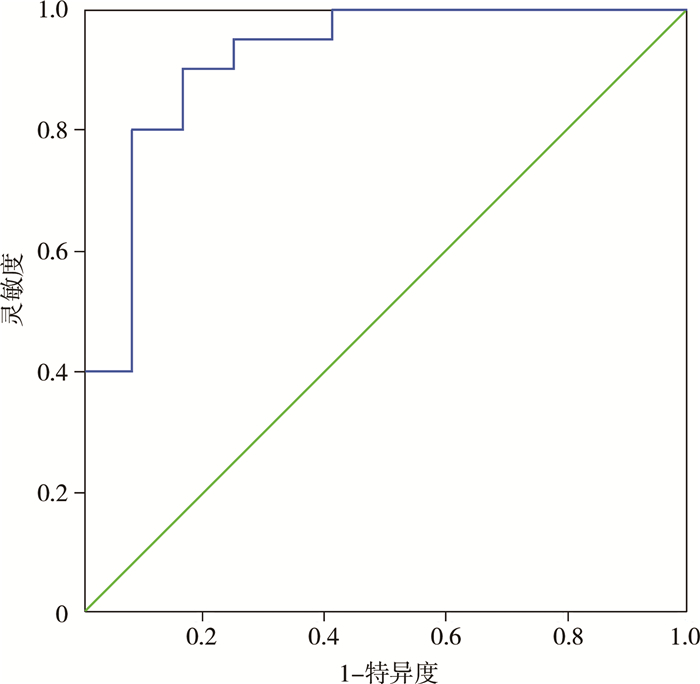

MRI-骨性TSL非连续组RAD的发生率为90.4%(47/52),明显高于MRI-骨性TSL连续组的25.0%(4/16),差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。两组间CR时的AI、年龄、性别、和IHDI分型差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。ROC曲线分析显示,正常侧与患侧AD的差值预测RAD发生的界值为0.31 cm,对应灵敏度和特异度分别为0.900及0.833,AUC为0.917。见表 3和图 3。

| 表 3 DDH患儿MRI-骨性TSL连续组与非连续组各参数比较 Table 3 Comparison of parameters between the MRI-bony TSL continuous and non-continuous groups in DDH children |

|

|

|

图 3 髋臼开口最大连线差值预测闭合复位后残余髋臼发育不良发生的受试者操作特征曲线 Fig.3 ROC curve for predicting residual acetabular dysplasia after closed reduction based upon maximal acetabular distance |

RAD可导致早期退行性关节疾病,是导致DDH手术效果不良的主要因素,到成人期则需要进行全髋关节置换。RAD在DDH患者中并不罕见,超过三分之一接受CR的DDH患者可发展成RAD。本研究中,RAD的发病率为75%(51/68),高于以往的研究报道[9, 22]。这可能是由于本研究随访时间较短和研究对象年龄较大。

RAD在早期阶段往往不表现出明显症状,其诊断主要依赖于X线检查。近来,放射学参数(如AI、CEA和RI等)被用于预测RAD的发生。然而,很大一部分DDH患儿在CR后早期CEA或RI正常,最终随访时可能会出现CEA或RI异常。此外,CEA和RI随时间的变化难以预测,且两者的测量都受股骨头形状的影响[9, 14]。国内一项多中心临床研究表明,AI是RAD最优质的预测因子。与CEA或RI相比,AI对于预测DDH患儿CR术后RAD的发生更具优势,其灵敏度、特异度和诊断准确性均较高[14]。但由于DDH患儿的X线片上有不规则和模糊的骨影,很难准确地标记出髋臼的外侧骨缘[14-15]。

当前,对于DDH的影像学诊断和术后评估,主要依赖于X线、CT和MRI成像等多种技术[9-11, 23]。MRI能够清晰展示关节软骨,对股骨头位置的评估尤为精确。此外,MRI不产生对人体有害的电离辐射,因此MRI在DDH的诊断和术前、术后评估中越来越受到青睐[12, 24-26]。在既往研究中,有学者在MRI影像上测量头部覆盖指数、髋臼头部指数等可以反映髋臼和股骨头匹配程度的指标,帮助判断闭合复位是否成功,也可通过动态评估这些指标在一定程度上预测CR的预后[13]。但是这些指标的测量过程较为复杂,且容易受到测试者主观因素的影响。本研究中,我们试图找到一个更可靠、更容易测量的参数。

本研究结果显示,髋关节MRI-骨性TSL可预测DDH患儿CR后RAD发生。与CEA、RI和AI相比,MRI骨性TSL不受股骨头形状的影响,不需要确定股骨头中心和髋臼外侧骨缘的确切位置,可用于单、双侧病例。但是,MRI-软骨性TSL术后均显示连续,对于预测髋关节CR术后RAD的发生并无价值。此外,X线-TSL与MRI-骨性TSL相比,其中5例X线-TSL显示不连续,而髋关节MRI-骨性TSL显示连续,最终患儿未发生RAD, 而且X线-TSL连续出现的时间较晚。MRI-骨性TSL可以更早、更准确预测RAD的发生,体现了MRI在观察TSL上更具优势。这是因为MRI检查分辨率更高,可展现任意断面图像,而X线检查只能显示二维结构,故对DDH患儿CR术后的治疗效果及术后预后评估存在局限性。

MRI可以很好地观察关节软骨的功能形态,补充其他检查所不能提供的髋关节软组织解剖结构,并可展现任意断面图像。既往研究表明,MRI可定量分析骨性髋臼指数和软骨性髋臼指数,可以更好地反映髋臼对股骨头的包容情况[22]。本研究中我们同样利用MRI极佳的软组织分辨能力,选取在横断面上测量髋臼两端软骨最突出点连线(即AD)。结果发现,在单侧病例中,正常侧与患侧AD差值也可作为RAD的一个预测因子(P=0.006)。ROC曲线显示AD差值预测RAD发生的灵敏度和特异度均较高,AUC为0.917,这说明正常侧与患侧AD差值可以很好地预测CR后RAD发生;正常侧和患侧AD的差值大于0.31 cm时,CR后容易发生RAD。这一数值使CR后RAD发生的预测更加具体、准确,且易于操作。同时,本研究发现IHDI分型也是RAD发生的危险因素,与既往研究相符[12]。但本次研究显示,AI不是RAD发生的显著预测因子,这一结论与前述研究存在差异,可能与样本数较少有关[14]。

本研究为单中心回顾性研究,病例数量少,随访时间短,具有一定的局限性。未来需要更多的患者和更长的随访时间来进一步验证。综上所述,IHDI分型、MRI-骨性TSL连续性以及正常侧和患侧AD差值可作为预测DDH患儿CR后发生RAD的指标。

利益冲突 所有作者声明不存在利益冲突

作者贡献声明 裴胤志、宁波负责研究的设计、实施和起草文章;裴胤志、吴春星进行病例数据收集及分析;裴胤志、宁波、黄鹏负责研究设计与酝酿,并对文章知识性内容进行审阅

| [1] |

Shipman SA, Helfand M, Moyer VA, et al. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: a systematic literature review for the US Preventive Services Task Force[J]. Pediatrics, 2006, 117(3): e557-e576. DOI:10.1542/peds.2005-1597 |

| [2] |

Kuitunen I, Uimonen MM, Haapanen M, et al. Incidence of neonatal developmental dysplasia of the hip and late detection rates based on screening strategy: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(8): e2227638. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.27638 |

| [3] |

Ortiz-Neira CL, Paolucci EO, Donnon T. A meta-analysis of common risk factors associated with the diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns[J]. Eur J Radiol, 2012, 81(3): e344-e351. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.11.003 |

| [4] |

Sharrock MN, Whelton CR, Paton RW. Selective sonographic scree-ning for developmental dysplasia of the hip-increasing trends in late diagnosis[J]. Acta Orthop Belg, 2023, 89(1): 15-19. DOI:10.52628/89.1.8636 |

| [5] |

Morris WZ, Hinds S, Worrall H, et al. Secondary surgery and residual dysplasia following late closed or open reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2021, 103(3): 235-242. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.20.00562 |

| [6] |

Albinana J, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, et al. Acetabular dysplasia after treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip.Implications for secondary procedures[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2004, 86(6): 876-886. DOI:10.1302/0301-620x.86b6.14441 |

| [7] |

Farsetti P, Caterini R, De Maio F, et al. Tönnis triple pelvic osteotomy for the management of late residual acetabular dysplasia: mid-term to long-term follow-up study of 54 patients[J]. J Pediatr Orthop B, 2019, 28(3): 202-206. DOI:10.1097/BPB.0000000000000575 |

| [8] |

Grissom L, Harcke HT, Thacker M. Imaging in the surgical management of developmental dislocation of the hip[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2008, 466(4): 791-801. DOI:10.1007/s11999-008-0161-3 |

| [9] |

Li YQ, Guo YM, Li M, et al. Acetabular index is the best predictor of late residual acetabular dysplasia after closed reduction in developmental dysplasia of the hip[J]. Int Orthop, 2018, 42(3): 631-640. DOI:10.1007/s00264-017-3726-5 |

| [10] |

Zhang ZL, Fu Z, Yang JP, et al. Intraoperative arthrogram predicts residual dysplasia after successful closed reduction of DDH[J]. Orthop Surg, 2016, 8(3): 338-344. DOI:10.1111/os.12273 |

| [11] |

Takeuchi R, Kamada H, Mishima H, et al. Evaluation of the cartilaginous acetabulum by magnetic resonance imaging in developmental dysplasia of the hip[J]. J Pediatr Orthop B, 2014, 23(3): 237-243. DOI:10.1097/BPB.0000000000000032 |

| [12] |

Wakabayashi K, Wada I, Horiuchi O, et al. MRI findings in residual hip dysplasia[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2011, 31(4): 381-387. DOI:10.1097/BPO.0b013e31821a556e |

| [13] |

Druschel C, Placzek R, Selka L, et al. MRI evaluation of hip containment and congruency after closed reduction in congenital hip dislocation[J]. Hip Int, 2013, 23(6): 552-559. DOI:10.5301/hipint.5000070 |

| [14] |

Kim HT, Kim JI, Yoo CI. Diagnosing childhood acetabular dysplasia using the lateral margin of the sourcil[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2000, 20(6): 709-717. DOI:10.1097/00004694-200011000-00003 |

| [15] |

Erkula G, Celikbas E, Kilic BA, et al. The acetabular teardrop and ultrasonography of the hip[J]. J Pediatr Orthop B, 2004, 13(1): 15-20. DOI:10.1097/00009957-200401000-00003 |

| [16] |

Smith JT, Matan A, Coleman SS, et al. The predictive value of the development of the acetabular teardrop figure in developmental dysplasia of the hip[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 1997, 17(2): 165-169. DOI:10.1097/00004694-199703000-00005 |

| [17] |

Walter SG, Endler CHJ, Remig AC, et al. Correction to: risk factors for failed closed reduction in dislocated developmental dysplastic hips[J]. Int Orthop, 2021, 45(11): 3009. DOI:10.1007/s00264-021-05124-z |

| [18] |

Walter SG, Bornemann R, Koob S, et al. Closed reduction as therapeutic gold standard for treatment of congenital hip dislocation[J]. Z Orthop Unfall, 2020, 158(5): 475-480. DOI:10.1055/a-0979-2346 |

| [19] |

Huang P, Wang DH, Mo YQ, et al. Teardrop and sourcil line (TSL): a novel radiographic sign that predicts residual acetabular dysplasia (RAD) in DDH after closed reduction[J]. Transl Pediatr, 2022, 11(4): 458-465. DOI:10.21037/tp-21-401 |

| [20] |

Morbi AHM, Carsi B, Gorianinov V, et al. Adverse outcomes in infantile bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2015, 35(5): 490-495. DOI:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000310 |

| [21] |

Narayanan U, Mulpuri K, Sankar WN, et al. Reliability of a new radiographic classification for developmental dysplasia of the hip[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2015, 35(5): 478-484. DOI:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000318 |

| [22] |

Mansour E, Eid R, Romanos E, et al. The management of residual acetabular dysplasia: updates and controversies[J]. J Pediatr Orthop B, 2017, 26(4): 344-349. DOI:10.1097/BPB.0000000000000358 |

| [23] |

Kim HT, Kim JI, Yoo CI. Acetabular development after closed reduction of developmental dislocation of the hip[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2000, 20(6): 701-708. DOI:10.1097/00004694-200011000-00002 |

| [24] |

Gotoh E, Tsuji M, Matsuno T, et al. Acetabular development after reduction in developmental dislocation of the hip[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2000, 378: 174-182. DOI:10.1097/00003086-200009000-00027 |

| [25] |

Zamzam MM, Kremli MK, Khoshhal KI, et al. Acetabular cartilaginous angle: a new method for predicting acetabular development in developmental dysplasia of the hip in children between 2 and 18 months of age[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2008, 28(5): 518-523. DOI:10.1097/BPO.0b013e31817c4e6d |

| [26] |

Miyake T, Tetsunaga T, Endo H, et al. Predicting acetabular gro-wth in developmental dysplasia of the hip following open reduction after walking age[J]. J Orthop Sci, 2019, 24(2): 326-331. DOI:10.1016/j.jos.2018.09.015 |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23