2. 首都儿科研究所附属儿童医院新生儿外科,北京 100020

2. Department of Neonatal Surgery, Affiliated Children's Hospital, Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing 100020, China

先天性膈疝(congenital diaphragmatic hernia, CDH)是新生儿常见先天性结构(膈肌发育缺陷)畸形之一[1]。研究表明,活产新生儿中CDH患病率约为2.5/10 000[2]。我国产前超声检查可提示50%~85%的先天性膈疝[3]。然而,目前关于CDH患儿预后的危险因素评估多集中于产前,产后评估的相对缺乏限制了新生儿外科医师为CDH患儿制定个体化的治疗措施[4]。本研究通过回顾性分析CDH患儿的术前超声声像图,探讨膈肌缺损最大长度、肝脏及胃泡位置、疝囊、肺发育情况等指标与CDH患儿预后的关系,为CDH的精准诊疗提供科学依据。

资料与方法 一、研究对象本研究为回顾性研究,收集2018年1月至2022年12月首都儿科研究所附属儿童医院新生儿外科诊治的92例≤3月龄的CDH患儿作为研究对象。病例纳入标准:①出生后行超声检查并经手术证实为CDH;②患儿均于超声诊断后48~72 h,呼吸、循环稳定情况下手术;③年龄≤3个月。排除标准:①存在食管裂孔疝;②合并需手术干预的心脏结构异常;③合并其他肺部病变(如肺囊腺瘤、隔离肺等);④患儿母亲有宫内治疗史。手术指征主要包括:氧浓度(fraction of inspiration O2, FiO2)<50%时,导管前血氧饱和度(pulse oxygen saturation, SpO2)维持在85%~95%,平均动脉血压维持在相应胎龄范围内,乳酸浓度<3 mmol/L;尿量>1 mL·kg-1·h-1。本研究获得首都儿科研究所附属儿童医院伦理委员会审核批准(SHERLLM2022035)。患儿家属均知情并签署知情同意书。

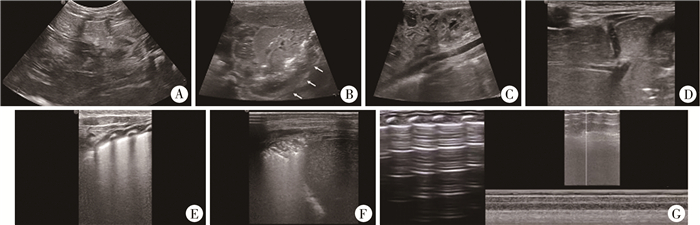

二、超声检查收集患儿出生身长、出生体重、性别、母亲分娩方式、孕周及有无合并症等。检查均由具有10年以上经验的儿科超声医师进行,仪器为彩色多普勒超声诊断仪(美国GE公司LOGIQ E11),选择L9线阵和C5-1凸阵探头(频率分别为9 MHz和1~5 MHz),进行以下超声检查(图 1):①上腹部横切面扫查:观察膈肌形态、位置、回声及运动,测量膈肌缺损最大长度、观察肺下界;②胸背部扫查:观察和分析肺部发育(有无气胸、肺间质水肿、肺不张)、有无胸腔积液、疝入内容物结构和形态,重点观察有无肝脏部分或全部疝入胸腔,胃泡是否疝入胸腔,有无疝囊,并观察心脏位置有无偏移;③上腹部或侧腰部冠状切面扫查:观察胃、肝、肾、脾、肠管的位置,以及有无形态改变。

|

图 1 先天性膈疝的超声诊断 Fig.1 Ultrasonic diagnosis in congenital diaphragmatic hernia children 注 A:测量膈肌缺损长度;B:观察有无疝囊(有疝囊);C:观察疝内容物(内容物为肠管,无肝脏疝入);D:观察疝内容物(见部分肝脏疝入胸腔);E:显示肺间质水肿(见自胸膜线发出并与之垂直的亮带);F:显示肺不张(见支气管充气征);G:显示气胸(肺点冰冻征,动态观察见胸膜滑动征消失) |

本研究将存在气胸、肺间质水肿或肺不张中任意一种表现定义为肺部超声异常;气胸、肺间质水肿及肺不张的超声诊断标准参照《新生儿肺脏疾病超声诊断指南》[5]。

三、统计学处理采用SPSS 21.0进行数据整理和分析。连续型变量(如出生体重、身长)采用M(Q1, Q3)表示,组间比较采用秩和检验。分类变量(如分娩方式、孕周)采用频数、构成比表示,组间比较采用χ2检验。采用二元Logistic回归分析膈肌缺损最大长度、肝脏、肺发育情况(有无气胸、肺间质水肿和肺不张)及胃泡位置和疝囊等指标与CDH结局的关联。采用Kappa检验比较膈肌缺损长度、肝脏位置、疝囊、肺部超声异常及上述四者联合诊断结果与CDH结局之间的一致性。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果本研究共纳入92例CDH患儿,其中男52例(56.5%)、女40例(43.5%)。92例中,存活组70例、死亡组22例,病死率为23.9%(22/92),主要死因包括持续肺动脉高压、支气管肺发育不良、肾衰竭等。

死亡组与存活组在出生体重、出生身长、性别、分娩方式和孕周等方面的差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05);死亡组中有合并症的患儿所占比例高于存活组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。见表 1。

| 表 1 死亡组与存活组先天性膈疝患儿的基本特征 Table 1 Characteristics of congenital diaphragmatic hernia between death and survival groups |

|

|

死亡组中肝脏疝入胸腔和肺部超声异常的人数比例高于存活组,存活组中有疝囊者所占比例高于死亡组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);两组膈肌缺损最大长度、胃泡位置及膈疝位置差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 存活组与死亡组先天性膈疝患儿超声指标比较 |

|

|

Logistic回归分析发现,膈肌缺损大于4 cm、肝脏疝入胸腔、肺部超声异常及无疝囊是CDH预后的独立影响因素(P<0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 先天性膈疝死亡影响因素的多因素Logistic回归分析 Table 3 Logistic regression analysis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia death |

|

|

以CDH死亡为结局,膈肌缺损>4 cm、肝脏疝入、无疝囊和肺部超声异常预测CDH死亡的一致性较低,Kappa值分别为0.351,0.522、0.557和0.563。而四者联合预测CDH死亡的一致性较高,Kappa值达0.788(P<0.001),且灵敏度和特异度均较高,分别为98.6%和81.8%。见表 4。

| 表 4 膈肌缺损>4 cm、无疝囊、肝脏疝入、肺部超声异常及四者联合预测先天性膈疝死亡的价值 Table 4 Predictive value of diaphragmatic defect > 4 cm, an absence of hernia sac, hepatic hernia, lung ultrasonic abnormalities and the combination of four indicators for predicting death from congenital diaphragmatic hernia |

|

|

CDH是由于胎儿在4~8周时膈肌发育停顿造成膈肌缺损,腹腔脏器疝入胸腔而导致的一种先天性疾病[1]。近年来,由于辅助技术的不断发展(如产后胸腔镜微创膈疝修补术和产前胎儿镜下气管堵塞术等),CDH患儿的病死率已明显下降[6]。与既往研究类似,本研究中CDH总病死率为23.9%[7-8]。

本研究发现肝脏疝入为CDH患儿死亡的危险因素之一。Werneck Britto等[9]基于77例CDH患儿的研究发现,与有肝脏疝入的CDH相比,无肝脏疝入的CDH存活率高出50%。Volpe等[10]基于110例CDH患儿的研究发现,肝脏疝入的CDH患儿较未疝入的患儿具有更大的脐静脉偏斜角。肝脏疝入可增加CDH患儿死亡风险的可能原因是肝脏处于右侧腹腔,如左侧CDH出现肝脏疝入,说明膈肌缺损面积较大,预后较差;如右侧CDH出现肝脏疝入,则加重了对肺部的实质性压迫,进一步影响肺部发育,最终导致CDH的不良结局。

CDH患儿疝囊的形成是由于腹内脏器通过胸腹裂孔处时仅有薄弱的胸腹膜(一些结缔组织或稀少的肌肉组织)而进入同侧胸腔所致[11]。研究认为疝囊是由于胸腹膜裂孔闭合后,肌肉组织未能及时发育所致[12]。Hagadorn等[13]基于70例CDH患儿的研究发现, 有疝囊的患儿存活率高于无疝囊的患儿(94.4%比67.3%,P=0.03)。Gentili等[14]也发现有疝囊组患儿存活率高于无疝囊组患儿(100%比32%,P<0.001)。与以往研究一致,本研究发现无疝囊为CDH患儿死亡的独立危险因素。疝囊的存在提高CDH患儿生存率的潜在机制可能是疝囊在一定程度上避免了腹腔内脏器进入胸腔, 从而减轻了胸腔内脏器的受压迫程度[15]。

膈肌缺损大小通常是用于评估CDH患儿膈肌发育的最直观指标。基于140例CDH患儿的研究发现,膈肌缺损较大的CDH患儿预后较差[16]。本研究同样发现膈肌缺损长度较大是CDH患儿死亡的危险因素。此外,既往研究显示,合并肺部疾病的CDH患儿具有更高的死亡风险,这与本研究结果一致[17]。既往一项研究基于不同指标构建CDH预后评分体系,可较为准确地预测CDH预后情况,然而该体系主要集中探讨产前相关指标预测CDH患儿的预后[18]。本研究结果显示,上述4项产后超声评价指标(即膈肌缺损长度、肝脏位置、疝囊和肺部超声异常)均为CDH的危险因素,鉴于单个因素预测CDH的一致性较差,本研究通过联合上述指标发现,多指标联合可大幅度提高预测的准确性。

本研究存在一定的局限性:首先,单中心研究限制了结果的外推性;此外,本研究未能纳入CDH患儿产前超声的相关指标,如肺头比等。今后可基于多中心研究,以本研究超声指标为基础,联合产前超声数据,搭建更完整的基于超声的CDH预后预测体系。

综上所述, 联合膈肌缺损长度、肝脏位置、有无疝囊及肺发育情况可更加准确地评估CDH患儿的死亡风险,在患儿出生后尽早识别、精准评估病程,以便临床医师及时调整治疗方案,进而改善结局,提高患儿存活率和生存质量。

利益冲突 所有作者声明不存在利益冲突

作者贡献声明 文献检索为刘琴、马立霜; 论文调查设计为刘琴、马立霜、任红雁; 数据收集与分析为刘琴、任红雁、王明雪、刘雨萌; 论文结果撰写为刘琴、马立霜; 论文讨论分析为刘琴、马立霜、王明雪

| [1] |

Longoni M, Pober BR, High FA, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia overview[M/OL]//Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. GeneReviews?[Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, 2020: NBK1359. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20301533/.

|

| [2] |

Chatterjee D, Ing RJ, Gien J. Update on congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. Anesth Analg, 2020, 131(3): 808-821. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004324 |

| [3] |

Durward A, Macrae D. Long term outcome of babies with pulmonary hypertension[J]. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 2022, 27(4): 101384. DOI:10.1016/j.siny.2022.101384 |

| [4] |

Hautala J, Karstunen E, Ritvanen A, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia with heart defect has a high risk for hypoplastic left heart syndrome and major extra-cardiac malformations: 10-year national cohort from Finland[J]. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2018, 97(2): 204-211. DOI:10.1111/aogs.13274 |

| [5] |

中华医学会儿科学分会围产医学专业委员会, 中国医师协会新生儿科医师分会超声专业委员会, 中国医药教育协会超声医学专业委员会重症超声学组, 等. 新生儿肺脏疾病超声诊断指南[J]. 中华实用儿科临床杂志, 2018, 33(14): 1057-1064. Division of Perinatology, Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association, Division of Neonatal Ultrasonic Society, Chinese Neonatologist Association, Chinese Medical Doctor Association, Division of Critical Ultrasonic Society, China Medicine Education Association. Guideline on Ultrasound in Diagnosing Pulmonary Diseases in Neonates[J]. Chin J Appl Clin Pediatr, 2018, 33(14): 1057-1064. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-428X.2018.14.005 |

| [6] |

Coughlin MA, Werner NL, Gajarski R, et al. Prenatally diagnosed severe CDH: mortality and morbidity remain high[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2016, 51(7): 1091-1095. DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.082 |

| [7] |

Cruz-Martínez R, Etchegaray A, Molina-Giraldo S, et al. A multicentre study to predict neonatal survival according to lung-to-head ratio and liver herniation in fetuses with left congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH): Hidden mortality from the Latin American CDH Study Group Registry[J]. Prenat Diagn, 2019, 39(7): 519-526. DOI:10.1002/pd.5458 |

| [8] |

Kim PH, Kwon H, Yoon HM, et al. Postnatal imaging for prediction of outcome in patients with left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. J Pediatr, 2022, 251: 89-97.e3. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.07.037 |

| [9] |

Werneck Britto IS, Olutoye OO, Cass DL, et al. Quantification of liver herniation in fetuses with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia using two-dimensional ultrasonography[J]. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2015, 46(2): 150-154. DOI:10.1002/uog.14718 |

| [10] |

Volpe N, Mazzone E, Muto B, et al. Three-dimensional assessment of umbilical vein deviation angle for prediction of liver herniation in left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2018, 51(2): 214-218. DOI:10.1002/uog.17406 |

| [11] |

Colvin J, Bower C, Dickinson JE, et al. Outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based study in Western Australia[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 116(3): e356-e363. DOI:10.1542/peds.2004-2845 |

| [12] |

Grover TR, Murthy K, Brozanski B, et al. Short-term outcomes and medical and surgical interventions in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. Am J Perinatol, 2015, 32(11): 1038-1044. DOI:10.1055/s-0035-1548729 |

| [13] |

Hagadorn JI, Brownell EA, Herbst KW, et al. Trends in treatment and in-hospital mortality for neonates with congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. J Perinatol, 2015, 35(9): 748-754. DOI:10.1038/jp.2015.46 |

| [14] |

Gentili A, Pasini L, Iannella E, et al. Predictive outcome indexes in neonatal congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2015, 28(13): 1602-1607. DOI:10.3109/14767058.2014.963043 |

| [15] |

Le Duc K, Mur S, Sharma D, et al. Antenatal assessment of the prognosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: ethical considerations and impact for the management[J]. Healthcare (Basel), 2022, 10(8): 1433. DOI:10.3390/healthcare10081433 |

| [16] |

Pagliara C, Zambaiti E, Brooks G, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: perinatal prognostic factors and short-term outcomes in a single-center series[J]. Children (Basel), 2023, 10(2): 315. DOI:10.3390/children10020315 |

| [17] |

Amodeo I, Borzani I, Raffaeli G, et al. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2022, 181(9): 3243-3257. DOI:10.1007/s00431-022-04540-6 |

| [18] |

Hedrick HL. Management of prenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia[J]. Semin Pediatr Surg, 2013, 22(1): 37-43. DOI:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2012.10.007 |

2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23