2. 潍坊市中医院脊柱外科(山东省潍坊市, 261041);

3. 中国科学技术大学附属第一医院神经电生理室(安徽省合肥市, 230036)

2. Department of Spine Surgery, Municipal Traditional Chinese Hospital, Weifang 261041, China;

3. Department of Neuroelectrophysiology Room, First Affiliated Hospital, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230036, China

多模式术中电生理监测(multimodal intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring, MIOM)包括经颅电刺激运动诱发电位(transcranial electric motor evoked potential, TceMEP)、体感诱发电位(somatosensory evoked potentials, SSEP)和术中自由运行肌电图(free-run EMG),这些监测技术是保障脊柱畸形手术顺利进行的一类安全、准确和可靠的技术[1-7]。TceMEP可以监测脊柱畸形手术中的脊髓缺血和神经损伤,该方法有效且灵敏度较高[5, 8-10]。SSEP可以有效评估脊髓背侧功能的完整性[11]。SSEP与TceMEP联合监测是目前脊柱脊髓手术中探测神经功能简便且有效的方法[12]。

此外,有研究发现Free-run EMG是监测脊髓机械性损伤的潜在方法[13, 14]。神经源性混合诱发电位(neurogenic mixed evoked potential, NMEP)也可用于监测各种类型患者的脊髓功能[15, 16]。并且在一些动物研究中,NMEP也被认为是监测感觉途径的一种方法[17]。不同的组合(TceMEP、SSEP、NMEP和free-run EMG)可用于监测各种脊柱外科手术中可能发生的脊髓/神经损伤。

近年来,一些研究已经开始关注小儿脊柱手术的MIOM[15]。但是,针对年龄<10岁的早发性脊柱侧凸(early-onset scoliosis, EOS),特别是<5岁EOS的MIOM研究并不多见。对于EOS脊柱截骨的复杂手术(例如全脊椎切除术、半椎体切除术),术中如何确保神经功能的安全性显得尤为重要。本研究旨在探索MIOM在EOS截骨手术中的可靠性、安全性以及一些特有的阳性判断方法,从而为EOS手术中提供安全可靠的神经功能变化信息,防止术后神经系统并发症。

材料与方法 一、临床资料本研究收集2015年9月至2016年12月由北京协和医院骨科收治的20例EOS和120例特发性脊柱侧凸(adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, AIS)患者作为研究对象,平均年龄(13.9±0.51)岁;20例EOS患儿中,男童14例,女童6例,年龄2~3岁,平均年龄(2.65±0.11)岁,手术方式为后路截骨短节段固定融合。EOS患儿术后的神经症状由2~3位外科医生详细评估,通过临床查体与手术前比较得出结果。

二、TceMEP监测使用多功能动态神经系统监测仪(Axon系统Inc, Hauppauge, NY)进行监测,刺激电极采用皮下针电极,安放位置按照国际标准10~20脑电图命名系统,刺激电极放置于C3、C4处。刺激模式为连续串刺激,包含5~7个单刺激,每个刺激时程为300~500 μs,刺激强度200~500 V,带通滤波30~3 000 Hz。记录电极置于双下肢拇短展肌(abductor hallucis, AH),对照电极置于上肢拇短展肌(abductor pollicis brevis, APB),记录的电信号为复合肌肉动作电位(compound muscle action potential, CMAP)。EOS患儿较青少年或成人往往需要更高的刺激强度才能获得较为可靠的TceMEP波形,因此通常需要反复调节刺激参数以达到最佳效果。记录时程为100 ms。诱发电位仪的安放尽量避开各监护仪器并妥善接地,以保证安全并排除干扰。电生理监测技术人员经过专业化培训,能够在手术过程中严密监测并记录关键手术步骤时的MEP状态。

三、SSEP监测刺激电极采用表面电极,上肢选取腕部正中神经,下肢选取踝部胫后神经。采用单个脉冲电刺激,频率为4.7 Hz,刺激间期200 μs,刺激强度上肢15~20 mA、下肢25~30 mA,刺激强度以足趾轻微抽动为宜,带通滤波为30~1 500 Hz,记录时程为100 ms,平均叠加200次。记录电极和参考电极均为针电极, 电极安放位置同样按照国际脑电图 10~20命名系统,皮层记录电极置于中央点(Cz),参考电极置于额极点(Fpz)。

四、Free-run EMGFree-run EMG可能是检测早期脊髓损伤的一种潜在工具[13, 14]。故所有患儿采用双侧Free-run EMG结合TceMEPs探测术中脊髓/神经功能。本研究中Free-run EMG扫描速度2 s/div,标尺50 μV。脊髓/神经根附近操作时对应的连续爆发肌电反应需要提示给术者。

五、麻醉方法采用丙泊酚(3 mg/kg)和芬太尼(2.5 μg/kg)与短效肌肉松弛剂和吸入剂(七氟醚或一氧化二氮)组合诱导全身麻醉。在诱导和插管后不再给予肌肉松弛剂或吸入麻醉剂。麻醉维持量是丙泊酚(5~8 mg·kg-1·h-1),瑞芬太尼(0.1 μg·kg-1·min-1)和总剂量为5~6 μg/kg的芬太尼(间歇输注)。

六、统计学处理采用SPSS统计软件(IBM SPSS19.0)进行数据的整理与分析,对于TceMEP的波幅采用均数±标准差(x±s)表示,采用独立样本t检验来比较EOS和AIS患儿TceMEP的波幅,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

|

|

表 1 EOS患儿手术方式和MIOM监测结果 Table 1 Surgical procedure of EOS children and MIOM monitoring results |

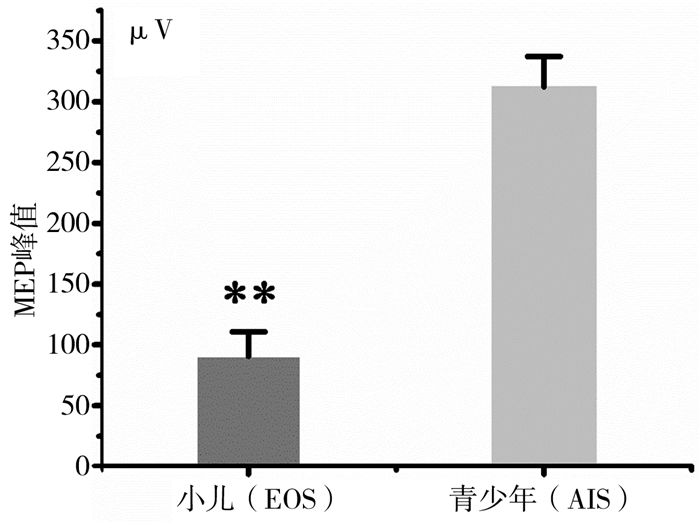

本项研究中,有95.0%(19/20)的患儿术中SSEP和TceMEP基线稳定可靠,只有1例在没有任何吸入剂(七氟醚或一氧化二氮)的全静脉麻醉(丙泊酚和瑞芬太尼)下无法记录有效的TceMEP基线。1例(病例16,表 2)在截骨手术期间出现TceMEP报警,在升高血压后很快转复。本组EOS病例中无一例术后神经系统并发症,EOS患儿平均TceMEP基线波幅为(88.7±21.9)μV(范围:27~278 μV),显著低于AIS患儿的(346.7±24.2)μV,差异有统计学意义(t=2.162, P < 0.01),见图 1。

|

Download:

|

| 图 1 EOS和AIS的TceMEP基线波幅对比 Fig. 1 Comparison of TceMEP baseline amplitude between EOS and AIS | |

先天性脊柱侧后凸畸形(congenital kyphoscoliosis, CKS)通常是进行性的,需要早期手术干预。截骨加短节段固定融合是针对此类EOS的常用方法[18]。对手术团队而言,截骨手术过程中的实时脊髓功能状态监测对于保证神经安全十分重要。本研究提示术中TceMEP和SSEP监测完全可以提供一种准确有效的方法来探测3岁以下幼儿脊柱畸形手术中的实时脊髓功能状态。

一、EOS中TceMEP的刺激阈值Fulkerson等[19]最近研究结果表明,TceMEP在儿童(年龄5~31个月,平均16.8个月)神经外科手术中监测脊髓运动通路是安全可靠的。年龄较小的幼儿需要更高的TceMEP阈值电压[(533±124)V,范围321~746 V]。Yang等[20]研究结果也包含类似观点(TceMEP阈值电压高达300~800 V)。本研究通过调节脉冲序列(5~7)和单脉冲刺激的持续时间(200~400 μs),可以达到相对低的TceMEP阈值(250~500 V),但该阈值仍远高于成人或AIS患儿,这可能与儿童运动神经通路发育不完全有关。因此,在EOS手术中往往需要更高的刺激强度来获得可靠的TceMEP基线。根据我们的经验和文献报道,较高的刺激强度不会给EOS患儿带来严重的神经系统或其他方面相关并发症[19]。但是刺激强度的上限至今还没有明确定论。

二、麻醉药物在MIOM中的作用近年来,有研究显示EOS基线成功率低、波幅低、诱发电压阈值高的原因可能是麻醉引起[20]。麻醉在EOS患儿术中神经功能监测中具有重要作用。术中TceMEP监测可以帮助我们避免仅使用SSEP监测可能出现的假阴性结果。但是,TceMEP监测对麻醉条件和其他系统性全身性因素(例如低血压、缺氧和贫血)非常敏感。通常麻醉医师在EOS手术中会使用醚类吸入剂,为了获得TceMEP基线,需要显著提高刺激阈值。这会造成无法获得有效的TceMEP基线,尤其在3岁以下EOS患儿中[20]。因为<3岁的EOS患儿TceMEP幅度要比成人或者青少年低很多,且醚类吸入剂更能抑制EOS患儿中的TceMEP波幅[19, 20]。

另外一种挥发性吸入麻醉剂一氧化二氮也可能导致EOS患儿无法获得TceMEP基线。有研究表明吸入剂(七氟醚或一氧化二氮)不仅抑制了TceMEP,而且降低了SSEP的幅度[21]。为了获得最佳的MIOM效果,在EOS手术中应尽量不使用任何吸入麻醉剂。本组截骨矫形手术中无一例使用任何吸入剂(七氟醚或一氧化二氮)。此外,静脉麻醉药丙泊酚的剂量也会通过影响麻醉深度来抑制术中TceMEP的波幅。当TceMEP发生不伴随高危手术操作的波幅变化时,可通过改变麻醉深度来补偿TceMEP丢失。

三、不同监测模式的互补作用有时,外科团队需要在脊柱截骨和矫形期间实时了解脊髓的功能状态,TceMEP相对SSEP而言避免了平均所需的时间,可以即刻得出监测结果,手术团队可以参考TceMEP结果及时采取行动以防止脊髓损伤。此外,有研究表明,TceMEP在监测脊髓运动功能上比SSEP更敏感[3, 8]。同时很少出现关于TceMEP假阴性的相关报道。当然SSEP在探测脊髓感觉功能上也具有诸多优势。EOS手术中TceMEP幅度往往非常低(通常低于150 μV),容易受系统性或其他因素干扰。SSEP则相对比较稳定,可在不明原因的TceMEP改变时,提供重要的脊髓功能补充信息。因此,TceMEP和SSEP各有优点,二者协同判断脊髓整体功能状态是目前EOS手术中较为实用的监测方法。

本项研究表明,在适当麻醉条件下,TceMEP、SSEP和Free-run EMG联合监测可为EOS患儿提供实时准确的脊髓功能信息。TceMEP可以提供实时可靠的神经功能信息,帮助外科医生手术中及时快速应对。且SSEP和Free-run EMG相对稳定,可为不明原因的TceMEP变化提供重要的补充信息。

| 1 |

Matsuoka R, Takeshima Y, Hayashi H, et al. Feasibility of adjunct facial motor evoked potential monitoring to reduce the number of false-positive results during cervical spine surgery[J]. J Neurosurg Spine, 2019, 1-8. DOI:10.3171/2019.9.SPINE19800. |

| 2 |

Ushirozako H, Yoshida G, Hasegawa T, et al. Characteristics of false-positive alerts on transcranial motor evoked potential monitoring during pediatric scoliosis and adult spinal deformity surgery:an "anesthetic fade" phenomenon[J]. J Neurosurg Spine, 2019, 1-9. DOI:10.3171/2019.9.SPINE19814. |

| 3 |

尹佳, 张珂, 林涛, 等. 早发性脊柱侧凸的手术治疗与并发症研究进展[J]. 临床小儿外科杂志, 2018, 17(9): 649-653. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6353.2018.09.003. Yin J, Zhang K, Lin T, et al. New research advances in surgical treatment and complications of early-onset scoliosis[J]. J Clin Ped Sur, 2018, 17(9): 649-653. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6353.2018.09.003. |

| 4 |

夏三强, 邱俊荫, 史本龙, 等. 伴与不伴脊髓空洞的Chiari畸形伴脊柱侧凸患儿脊柱矫形术中神经电生理监测的差异性[J]. 临床小儿外科杂志, 2018, 17(9): 659-663. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6353.2018.09.005. Xia SQ, Qiu JY, Shi BL, et al. Comparison of intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in Chiari malformation-associated scoliosis patients with or without syringomyelia[J]. J Clin Ped Sur, 2018, 17(9): 659-663. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6353.2018.09.005. |

| 5 |

Jahangiri FR, Asdi RA, Tarasiewicz I, et al. Intraoperative triggered electromyography recordings from the external urethral sphincter muscles during spine surgeries[J]. Cureus, 2019, 11(6): e4867. DOI:10.7759/cureus.4867. |

| 6 |

Lewis SJ, Wong IHY, Strantzas S, et al. Responding to intraoperative neuromonitoring changes during pediatric coronal spinal deformity surgery[J]. Global Spine J, 2019, 9: 15S-21S. DOI:10.1177/2192568219836993. |

| 7 |

Huang ZF, Chen L, Yang JF, et al. Multimodality intraoperative neuromonitoring in severe thoracic deformity posterior vertebral column resection correction[J]. World Neurosurg, 2019, 127: e416-e426. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.140. |

| 8 |

Wang SJ, Yang Y, Li QY, et al. High-risk surgical maneuvers for impending true-positive intraoperative neurologic monitoring alerts:experience in 3139 consecutive spine surgeries[J]. World Neurosurg, 2018, 115: E738-E747. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.162. |

| 9 |

Wang S, Li C, Guo L, et al. Survivals of the intraoperative motor-evoked potentials response in pediatric patients undergoing spinal deformity correction surgery:what are the neurologic outcomes of surgery?[J]. Spine, 2019, 44(16): E950-E956. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003030. |

| 10 |

Wang S, Tian Y, Zhang J, et al. Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring to patients with preoperative spinal deficits:judging its feasibility and analyzing the significance of rapid signal loss[J]. Spine, 2017, 1(6): 777-783. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2015.09.028. |

| 11 |

Zhuang QY, Wang SJ, Zhang JG, et al. How to make the best use of intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring? experience in 1162 consecutive spinal deformity surgical procedures[J]. Spine, 2014, 39(24): E1425-E1432. DOI:10.1097/Brs.0000000000000589. |

| 12 |

Skinner SA, Hsu B, Transfeldt EE, et al. Spinal cord injury from electrocautery:observations in a porcine model using electromyography and motor evoked potentials[J]. J Clin Monit Comput, 2013, 27(2): 195-201. DOI:10.1007/s10877-012-9417-2. |

| 13 |

Skinner SA, Nagib M, Bergman TA, et al. The initial use of free-running electromyography to detect early motor tract injury during resection of intramedullary spinal cord lesions[J]. Neurosurgery, 2005, 56: 299-314. |

| 14 |

Hu Y, Luk KD, Lu WW, et al. Application of time-frequency analysis to somatosensory evoked potential for intraoperative spinal cord monitoring[J]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2003, 74(1): 82-87. DOI:10.1136/jnnp.74.1.82. |

| 15 |

Wang SR, Zhang JG, Qiu GX, et al. Posterior hemivertebra resection with bisegmental fusion for congenital scoliosis:more than 3 year outcomes and analysis of unanticipated surgeries[J]. Eur Spine J, 2013, 22(2): 387-393. DOI:10.1007/s00586-012-2577-4. |

| 16 |

Vitale MG, Moore DW, Matsumoto H, et al. Risk factors for spinal cord injury during surgery for spinal deformity[J]. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 2010, 92(1): 64-71. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.H.01839. |

| 17 |

Journee HL, Polak HE, De Kleuver M. Conditioning stimulation techniques for enhancement of transcranially elicited evoked motor responses[J]. Neurophysiol Clin, 2007, 37(6): 423-430. DOI:10.1016/j.neucli.2007.10.002. |

| 18 |

Tamkus AA, Rice KS, Kim HL. Differential rates of false-positive findings in transcranial electric motor evoked potential monitoring when using inhalational anesthesia versus total intravenous anesthesia during spine surgeries[J]. Spine J, 2014, 14(8): 1440-1446. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.037. |

| 19 |

Fulkerson DH, Satyan KB, Wilder LM, et al. Intraoperative monitoring of motor evoked potentials in very young children Clinical article[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatri, 2011, 7(4): 331-337. DOI:10.3171/2011.1.Peds10255. |

| 20 |

Yang J, Huang Z, Shu H, et al. Improving successful rate of transcranial electrical motor-evoked potentials monitoring during spinal surgery in young children[J]. Eur Spine J, 2012, 21(5): 980-984. DOI:10.1007/s00586-011-1995-z. |

| 21 |

Ferguson J, Hwang SW, Tataryn Z, et al. Neuromonitoring changes in pediatric spinal deformity surgery:a single-institution experience[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2014, 13(3): 247-254. DOI:10.3171/2013.12.PEDS13188. |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19